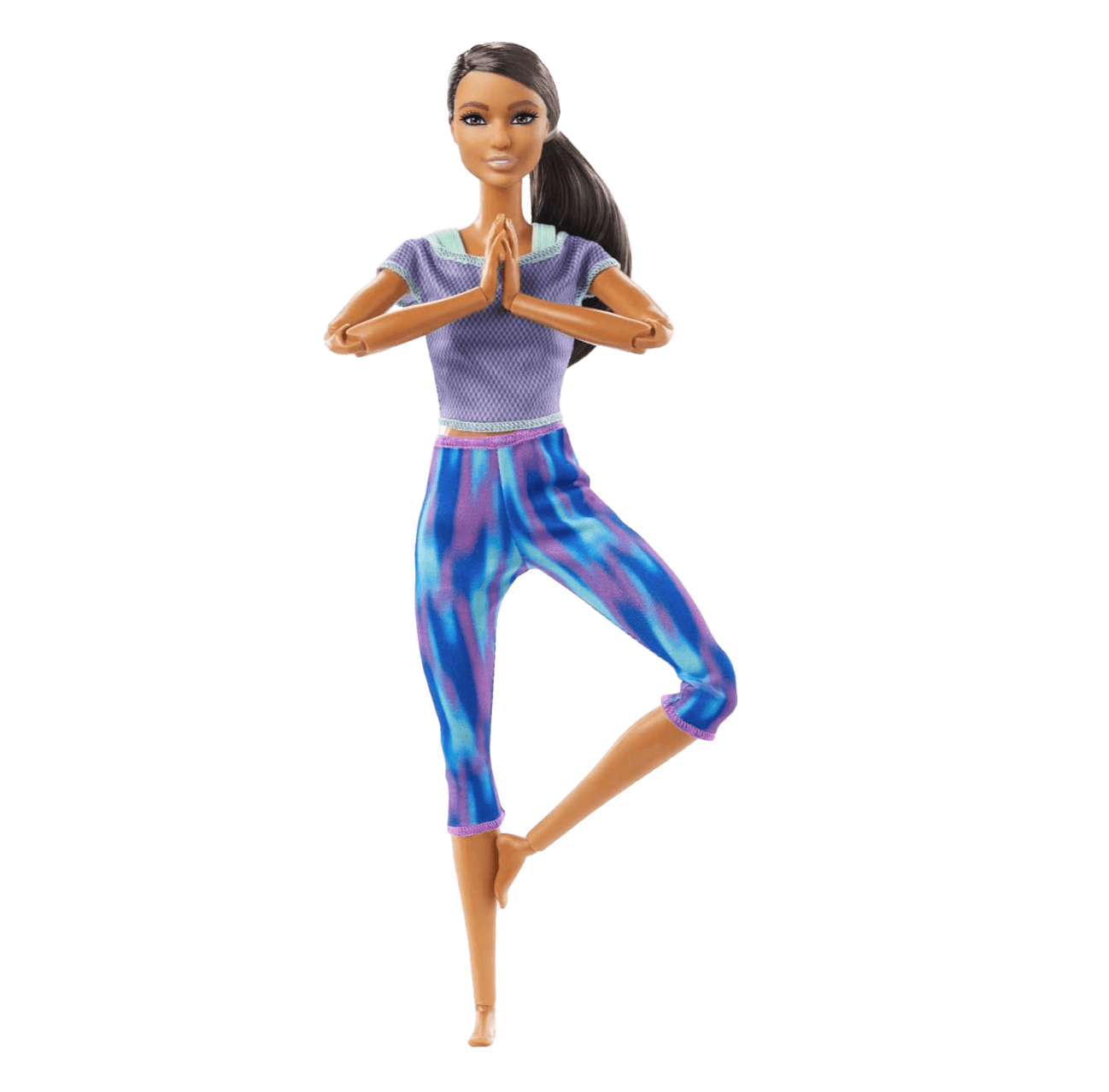

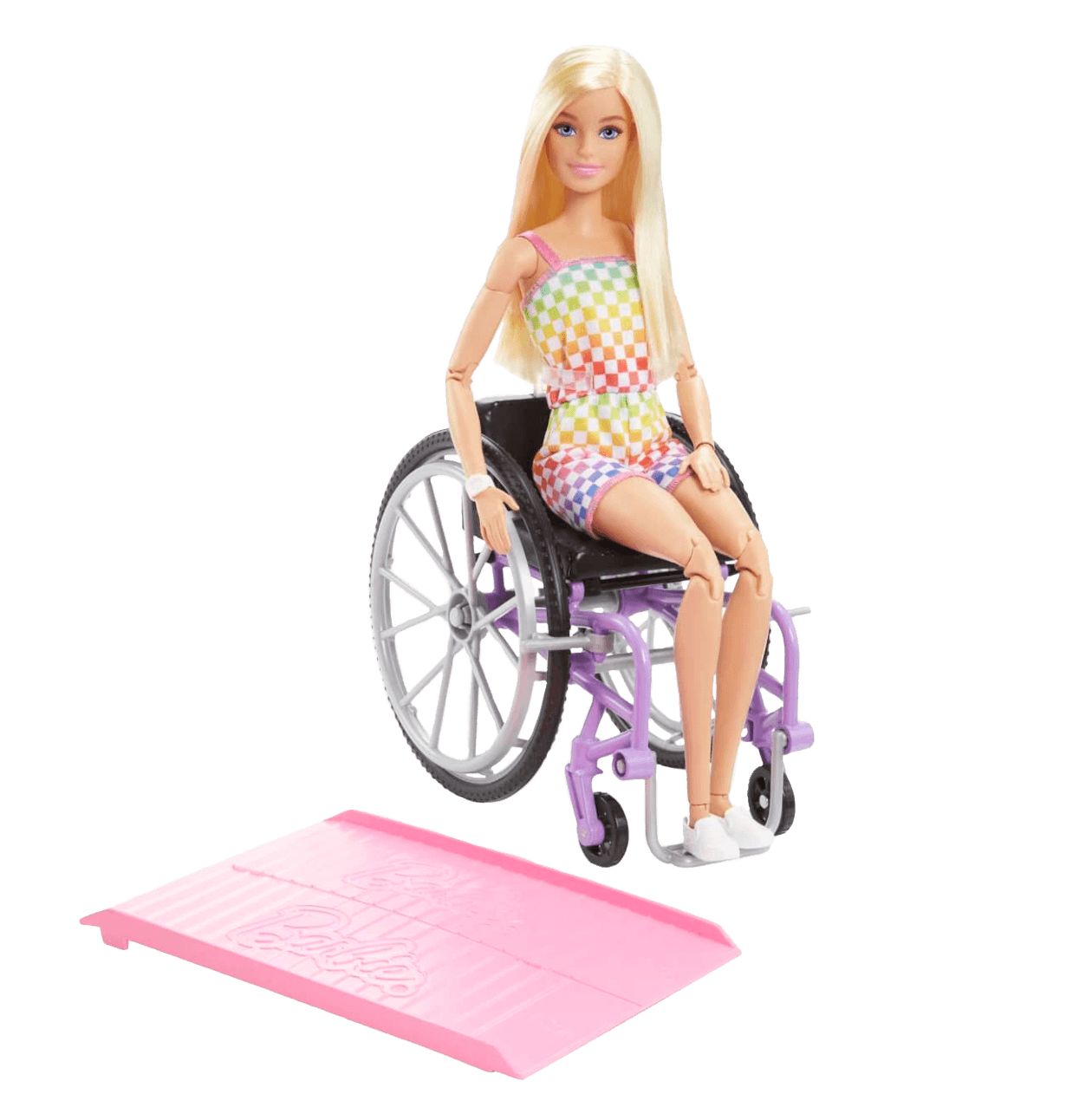

Few children’s toys have had as contentious an impact as Mattel Inc.’s Barbie doll. As the original fashion doll with a presence on the market since 1959, Barbie represents a complexity unknown by almost any other toy. In one way, Barbie represents the suppression of femininity through idealised beauty standards (specifically, she is usually the initial example of a thin, white, blonde body standard that young girls are introduced to) as well as the lack of diversity and inclusion within society’s infrastructure (the first Black barbie, named Christie, was only made in 1980) – on the other hand, Barbie is the baddie with many careers and multiple lives. In a male-dominated world, her counterpart Ken is merely a sidenote. As a response to declining sales, Mattel Inc. has released 35 skin tones into the Barbie universe since 2015. Now, there are Barbies in a variety of races, body-sizes, there are Barbies with Vitiligo and Barbies in wheelchairs. There are Barbies with varying hair textures and styles, and fashion-choices too that reflect a move beyond the ‘pink, femininity’ of Barbie’s earliest years.

My childhood was saturated with Barbie – my most favourite was my ‘Camper Van’ Barbie set that I got for Christmas one year. In the way that most children’s toys do, ‘playing Barbies’ is a form of imagination exercise. I remember specifically about Barbie, like other games such as ‘House-House’, these are experiences in which children are able to colour in their developing conception of the reality around them.

Specifically in my Barbie games, she and Ken were always getting divorced and there were always fiery and dramatic narratives; perhaps not dissimilar to the context of my own environment around six or seven years old. Then, there is the very sticky issue of Barbie’s appearance. Barbie has served as the cultural archetype of all the most harmful messaging to young girls for the last few decades. As Afua Hirsch writes of the disproportionately sized doll in her piece for The Guardian, “traditional Barbies represent the body shape of 1 in 100,000 real-life women, have a waist size 20cm smaller than a group of anorexia sufferers, and would have insufficient body fat to menstruate.”

That’s not even mentioning the research published in Body Image, a scientific journal, which hypothesised that “In both studies, girls who played with thin dolls experienced higher body size discrepancies than girls who played with full-figured dolls. Girls who played with full-figured dolls showed less body dissatisfaction after doll exposure compared to girls who played with thin dolls. Playing with unrealistically thin dolls may encourage motivation for a thinner shape in young girls.” Considering that Barbie has only seen recent revamp in inclusion – there are already two generations of people for whom Barbie subconsciously programmed their understanding of beauty. I wonder if there is a correlation between Barbie’s success in the late 1980s to early 2000s, and the era of thinness and celebration of eating disorder-physiques? Cue celebrities like Paris, Lindsay, Nicole, Kate and even Pam.

Then, there is a question about Barbie’s facial features. Mass-producing a doll perhaps comes with its manufacturing challenges and it can be said that Barbie’s facial structure is just an easy identifier of the brand’s signature. Still, the messaging is the same. With her almond shaped, mascara heavy eyes, tiny nose and lips; there is a singular beauty convention, even within the array of diverse Barbies now. Where is the real representation of how women look? What are we still teaching young girls about beauty – that there is only one to look to be accomplished, powerful, beautiful and fun? My own internalised thin-idealism and perception of beauty can be traced as early back as my time playing Barbies. This was then replaced by fashion models in magazines – and thus, my entire early development in childhood and teenhood was predicated on confirmation bias from the world around me. I am also a cis-gendered white woman in a body that holds privilege. Barbie’s role has been far more detrimental to young Black, Asian and girls of Colour.

Given all of this, how could Barbie truly serve as a feminist icon? Barbie has been presented in various professional roles, ranging from doctors and astronauts to engineers and computer programmers. By highlighting diverse careers and encouraging girls to imagine themselves in these roles, Mattel Inc have promoted the idea that women can pursue any profession they desire, emphasising empowerment of the aspirations of young girls with slogans like ‘You Can Be Anything’. In 1965, the first astronaut Barbie was introduced, at a time when women were very much still relegated to the patriarchal role of the ‘homemaker’. Barbie has also ventured into areas such as girls’ education and social activism.

In collaboration with organisations like Code.org, Barbie has launched initiatives to encourage girls’ interest in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. Mattel Inc. released dolls honouring inspiring women from various fields, such as Amelia Earhart, Frida Kahlo, and Katherine Johnson, which could serve as educational tools for girls to pursue their own passions. Barbie’s career-powered, skillset-varied legacy is well worth celebrating and has made the Barbie universe able to withstand the evolving values of modern society. We still have a long way to go before true representation of women is seen across institutions, with equal rights, equal pay and safety continuing to be barriers and far from the status quo.

While we are just ten days away from the Barbie Movie’s launch, the plot has been kept as a locked secret. Suggestions have been made that this film serves as Barbie’s personal reckoning with the artifice of her world. As the Apple description of the plot simply states, “To live in Barbie Land is to be a perfect being in a perfect place. Unless you have a full-on existential crisis. Or you’re a Ken.” Knowing Greta Gerwig’s style, we can expect to welcome some measure of chaos and flux to Barbie’s highly stylised existence and expression. Interestingly, the film has been co-signed with the Barbie™ brand as a kind-of collaboration. If the suspected contents of the film prove to be true, we might be witnessing a genuine effort by Mattel Inc to uncover and evolve the way Barbie can be understood by past, present and future fans. Through Barbie The Movie, us older generations of Barbie-players might even find a measure of healing for the ‘Barbie’ archetype embedding within our earliest subconscious programming. I’m excited for the film and to relish in the absurdity of ‘girliness’ – the sweetness and complexity of being a girl, too.

Courtesy of Mattel Inc.

Courtesy of Warner Bros.

Written by: Holly Beaton