I find the subject of Artificial Intelligence extremely intimidating, and I’m not sure I ever imagined putting together some array of perspectives on it. Like for many of us outside of the tech bubble (no matter how deeply influenced by said bubble that we may be), AI has, until recently, felt like a far-off dream; and yet, it is perhaps the singular force of futurism that we can conceive, and one of the wildest frontier of human evolution thus far – apart from space travel, and in my opinion, learning to cultivate fire; which pretty much set the tone for all of our advancements thereafter. Although the internet stands as the most analogous structure that we have created to the human brain – as a neurologically-like driven network of information reception and dissemination – Artificial Intelligence is the next step and in the last few months, its presence has ramped up – particularly in the creative and arts industries. With AI being a vast conversation, and having implications for so many different spheres of our life; I will be focusing mainly on the perspectives of artists, experts and its relationship to the creative industry. I will be focusing on the aspect of artificial intelligence that we are most acquainted with as the public; machine-learning.

Machine-learning AI, in its raw definition, is the simulation of human intelligence through the use of machinery. Artificial intelligence requires a base software that is programmed by people; and until (or if, obviously) AI gains sentience (that’s a whole different ball game), when we speak of AI – we are speaking of a system that derives its entire basis from the fine-tuning of human beings, through algorithmic coding. In the way that AI is useful, is its ability to somewhat transcend our own limitations of time and singular focus – as well as analyse incredible sweeps of information, arriving at conclusions of systems and processes, or in the case of this article – digest and generate art and writing based off near-infinite numbers of examples already created by human beings. Basically, very basically, we are teaching a system to mimic sentient human-thinking and thus teach itself, better than we can, to perform tasks, faster than we can. This may inevitably lead to the obsolescence of jobs and tasks. The fundamental question that keeps occuring to me in the AI-discourse is, are there any aspects of human life and ingenuity that we can deem truly sacred, such as art? And if so , is AI in direct opposition to this? These are ongoing questions and as subjective as the human experience is, so too is the debate on AI. There are those who are vehemently against it, those who are neutral, impartial and curious – and then there are those who are excited at this new frontier.

Images: Joshua Ben Longo

Early in January of 2023, news broke of a class-action lawsuit by a group of artists against Midjourney, Stable Diffusion and DeviantArt’s new AI art-generator, DreamUp; with each of these companies playing their roles in the creation of AI-art tools. As stated by Polygon.com, “The suit alleges that these companies “violated the rights of millions of artists” by using billions of internet images to train its AI art tool without the “consent of artists and without compensating any of those artists.” These companies “benefit commercially and profit richly from the use of copyrighted images,” the suit alleges. “The harm to artists is not hypothetical,” the suit says, noting that works created by generative AI art are “already sold on the internet, syphoning commissions from the artists themselves.” With no legal precedent as to navigate the very delicate issue of intellectual property rights, this is a landmark assertion by artists of the viewpoint that AI, as utilised by corporations and in the climate of late-stage capitalism, is a terrifying future. In a world where multi-nationals seem hellbent on sucking up resources and rights in the name of growth of profit, why would they ever want to consider the perspective of artists, least not their right to protection? As artist Natalie Paneng says, “I think with every technological advancements that we as artists have early exposure to, it always seems quite scary – the unknown is overwhelming. There seems to be a reactivity to it, especially the idea of a machine taking over the job of a person. For me, I feel very torn. A lot of my work springs from my lived experience growing up in the cyber-age, and I employ a lot of digital tools in my practice digitally, and physically. I am interested in AI as a tool, not as a generator of art; for me, what makes art interesting is that all these methods, mediums and themes link directly back to a person, and an individual’s mind, labour, effort and hands. So in that sense, AI-generated art is not valuable to me. AI-art looks like AI-art; and I’ve seen some cool stuff, but it lacks that essence that runs through every artist and their work.”

While AI doesn’t seem likely to offer any kind of the extra-dimensional quality of art itself – the inarticulate nature of how creativity manifests through us – this is not to say that it cannot be used (and is already being used) to dilute the participation of people in the very act of creating – if a company can use ChatGPT to write copy instead of paying a writer, why wouldn’t they? If a brand can generate a logo using an AI-tool, instead of paying a graphic designer, why would they concede to the overhead of hiring human beings? It is very difficult to have this conversation without understanding the hyper-competitive, cutthroat economic environment that we find ourselves in; and as such, AI is a dream come true for the exponential growth required for businesses, brands and their income-generation in a globalised, capitalist world.

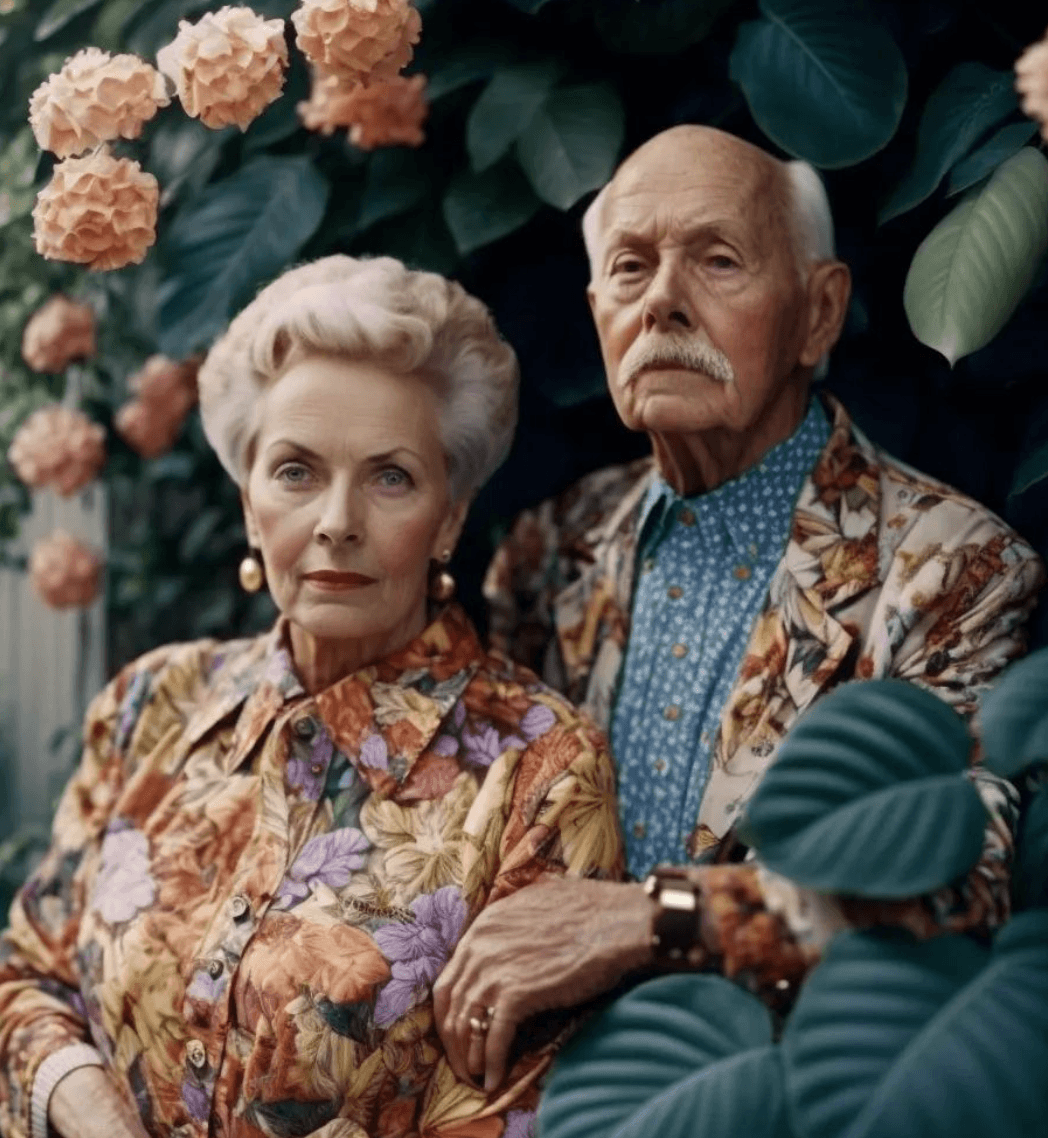

Images: Malik Afegbua

There a few schools of thought around the future of AI in this way – for one, that AI has the potential to free us from the means of production entirely – as Josh Hall puts it so seductively for Dazed, “Fully Automated Luxury Communism is the utopian idea that we’ll all fulfil our true human potential while robots do the work.’’ The other scenario is that AI will be used to facilitate the unchecked growth of our economic system, to the extent that much of the population in society are left utterly redundant to society’s creation, participation or benefit. It is difficult to extract any technology from its context; and much like the world wide web was intended to set us free, so any seemingly utopian and unimaginable technologies like AI would require a social, cultural and political landscape in which to be developed and nurtured. In a world where, despite being ‘richer’ (financially, technologically and resource-wise) than ever as a species, the largest swathes of economic divisions continue to worsen. When we speak of AI being able to assist creatives in their jobs tasks; it is easy to understand why there exists the fear that AI will overtake such jobs, entirely. As the wealthiest elite seek to get wealthier at whatever cost, AI perhaps presents a future where the overhead of paying labourers and workers ceases to exist completely – and it is hard to think of the idea of ‘fully automated luxury communism’ as, though sexy as it sounds, being remotely possible. Why would class divisions suddenly melt away because of AI, if AI is largely being expanded by elitist-strongholds in Silicon Valley – and a sudden change of heart is hard to imagine when the richest people in the world, like Elon Musk, hoard billions of dollars created by the labour of enslaved cobalt-miners in the DRC?

The anger and passion of artists has been a strong feature of the online discourse around AI-generated art. Keith Vlahakis is a Cape Town-based illustrator and artist, who counts digital methods as his primary mediums – however, the recent evocation by machine-learning artificial intelligence in the creative landscape is one that speaks to a larger, systemic technocracy, as he says, “I am strongly against AI art and all the software behind it, I don’t believe it should actually be called AI. This is more like “forgery” and theft on a global tech level. Several high level artists have already filed lawsuits against the tech companies developing the software. Stable diffusion is just a fancy word for a program that collages stolen work together, without consent. This topic is so nuanced that it needs to be unpacked at multiple levels, it’s not just about art – or the product generated by AI – it’s about the implications of ethical sacrifices. I also feel that it has revealed that there are a lot of imposters in our creative industry. Years ago I heard about “imposter syndrome” in art, and I always felt it was a way to over justify doubt and an unnecessary term really, but now as I see creatives who are willing to sacrifice the entire creative process in all its beauty to a “prompt?” It’s honestly appalling, heartbreaking and disappointing, and I never thought I would live to see such times. There are some imposters out there who are solely out to make a dollar off the skills and culture humanity collectively has taken thousands of years to develop.” As someone whose practices exist within the digital space, it has also sparked Keith to question some co-occurring themes, saying, “I will never endorse AI art and to a certain extent, I have lost all my respect for the NFT market.”

Images: Floral Fiction by David Schild

It became clear in my research and communication with artists on this subject that there are two scenarios cascading into the creative community – often, the two are imperceptible. These are the application of AI technology by artists themselves, in the way that a designer employs Photoshop or InDesign; and then there are the companies using the referential material of artists’ work, to generate copy and paste style graphics. As Natalie says, “The thing I fear the most, is AI generating the style of artists. I think there needs to be education and discourse around how we can protect our work as artists, while not allowing fear to be a barrier to exploring AI as a methodology in our practices. It is bigger than us, but we need to find ways to cultivate that AI can be actually useful and not harmful.” Designer, photographer and artist Koos Groenewald undertook his own process of diving into AI as a way to quell his own anxieties, explaining, “I mostly knew about all of this superficially, only the top layer of noise, and this recent rumbling of noise made me super scared. Before getting stuck into it, it just seemed like AI could basically do anything that we as artists, designers and writers can do, and so it would obviously replace us all by the end of the next year. After joining the MidJourney Discord and navigating the initial confusion – I actually got super excited. It’s just so damn impressive what it can do in basically no-time. Especially if you consider what people my age had to do in ad agencies to make comps of people doing things, bad stock libraries and so on – all those days of work in seconds, really.”

With the spirit of curiosity and open mindedness, Koos soon realised something which I had not understood yet myself – that AI as a technology for creative pursuits, still a requires highly skilled artist, “With this excitement I messed around and tried to copy some of the famous AI artists to see how ‘easy’ it is to create ‘the work’. With some better and worse results – and made me realise that the artists using the AI are still super skilled and that the best ones take time, skill and originality in creating and guiding the AI. I then had big stars in my eyes because I had a massive illustration job to start and I assumed Midjourney could easily create the brief, a ‘Fictional Utopian Future city-scape of Amsterdam’, for me to work from – but after 4 hours of trying to get it, I really hadn’t gotten anywhere useful or useable and realised that, ironically, if I’d just drawn for 4 hours I’d probably have been done by now. So for now my job feels safe – and like all tools it still needs a creative ‘wrangler’ to get certain and required creative results. As long as humans are the audience the human ‘touch’ is a valuable translation, I think when the AI starts making art for itself then maybe – damn – then who knows what kind of fucked we’ll even be? I went from scared to excited, to disappointed, back to scared but also realistically excited. I guess it weirdly also made me see how much AI has been in our lives already with less outrage, which makes this feel reassuringly like an evolution.”

Koos’ experience speaks to the source of the fear, perhaps, for us who are outside of AI and particularly those of us outside of the tech industry; these are unknowable terrains that present multiple timelines and outcomes and with such little relative agency that we all have in an ever-changing, hyper-fast timeline – what happens if and when AI is no longer a system that needs human beings? Tim Jamboula, an innovation consultant & disruptive technology researcher, with an extensive background in AI – comments that this fear, and our inability to comprehend it, is precisely the point of why AI can exist so impactfully in our lives, “our brain does not operate, work, or think exponentially. We, human beings do not have the ability to comprehend the full extent of exponentials. AI from now on, with all the data it has at its disposal will accelerate technological and human progress in various ways, within just the next 2-5 years. An imaginary vision of the state of the world by then is hard to fathom, due to our inability to process information exponentially.” While this may be exciting, Tim and other experts in his field believe that legal due process such as lawsuits, are actually a necessary building block to the regulation and streamlining of AI as integrated into our lives, saying, “as much as it brings forth great opportunities, it, like everything else, gives birth to new challenges, we as a society have to face. Of course, we will need regulations to counter IP rights and further infringements, or other ethical issues. The new Bing + ChatGPT fusion will most definitely lead to further lawsuits down the line, once website owners or bloggers or others do not get as much traffic onto their websites, as they used to. Deep fakes, digital identity thefts, and fake news among others are topics that are going to be of serious concern. Hence, regulators need to increase their efforts in comprehending this disruptive technology faster than before, in order to regulate it with clear boundaries. Besides, AI is here already. It regardless will affect all our lives. Thus posing the question of how to prepare for it?’’

Images: Past Futures by David Schild

I heard recently on the radio – and I forget who said it – that, “AI won’t take over the world, but people who can yield AI really well, might.” If there is one thing I have come to understand as I grow up on planet earth – it’s that letting go and surrendering, is sometimes all we can do. This is not to say that we should abide by whatever arises in the world; but rather, that there is a measure of embrace to be had, but also righteous anger and questioning, especially when it comes to technology as a tool of governments and institutions. I find AI eerie, still, but profoundly less so than before; I suppose that could be a consequence of Google Drive being the full summary of my technological abilities. Perhaps it’s also because I interact with brilliant creatives everyday, and to me – it’s going to take a lot more than a machine (however brilliant) to triumph over the magic of human beings. Maybe I’m an eternal optimist – and maybe I have to be in order to get by – but I will leave you with a last piece of advice by Tim, on how industry professionals can start adapting to this new frontier, should they wish, “It all starts with recognising AI as what it is. It is a helper and an assistant in its simplest form. Meaning it will not completely replace you, but rather take over big chunks of your work. Moreover, professionals have to evaluate their field of work and their daily tasks, to determine the tasks that can be automated and taken over by AI. The ones that turn out to be difficult to automate, which are most of the time, generalistic tasks, should be focused on and built upon. Subsequently, it does not hurt to maybe acquire future-orientated qualifications or skills, because AI creates new jobs too. Apart from that, professionals should aim to become better at asking questions/prompts and connecting patterns or identifying related connections.”

/// For Further Reading:

Artificial Intelligence Art from African and Black Communities

Nigerian Artist Malik Afegbua uses AI to celebrate the Elderly

MidJourney Sued for Severe Copyright Infringements

How To Spot AI Art, According to Artists

What is the next frontier or AI and Robotics?

Unpacking The Legal Side of AI in South Africa

Images by the following AI artists:

Koos Groenewald @koooooos Joshua ben Longo @longoland Malik Afegbua @slickcityceo David Schild @diewithregret

Written by: Holly Beaton

Published: 21 February 2023