Buqaqawuli Nobakada’s mixed media works are poignant expressions of the Black, female experience. Her works define what it means to be a woman – that contemplative, tender resolve that embodying femininity often asks of us, and what it means to take up space, and the responsibility of this. For Buqaqawuli, her forthright purpose as an artist is to craft imagery that younger girls may see, especially Black girls, and realise that those foregrounds are precisely the spaces that they can inhabit. In our conversation below, Buqaqawuli’s retrospection of her work depicts the precise and critical need that art serves; art is not frivolous, it is an inherent requirement for shifting, healing and articulating the consciousness of human beings. On the matter of who she paints for, Buqaqawuli describes why her recents works showcase luxury settings, “I had a conversation with a cousin of mine who comes from the context I started in and I remember telling her I wanted a house with an infinity pool and she didn’t understand what that was, and I decided that that’s the kind of thing I want to paint. She’s never seen someone that looks like her in that sort of space, owning or existing around those kind of things so she can’t dream it or work towards it because even if she looks through a magazine with luxury homes, the little white picket fence family in the magazine doesn’t look like her or anyone in her immediate surrounding so she grows up thinking she doesn’t deserve to live like that or she doesn’t belong there: that’s the thing I want to change. That’s why I paint the girls in the fast cars and lace fronts, so my younger self can dream.”

Toward her professional emergence in the art world, Buqaqawuli is a fine artist for whom I feel destiny will be made manifest. There is no greater alchemy than the kind of intellectual and social depth that Buqaqawuli demonstrates in our conversation – I will leave the rest of your understanding of Buqaqawuli, in her own words, below.

How did you arrive at being an artist – what were some of the most formative moments that showed you that this was your path?

It’s interesting because on a craftsman level it’s something I’ve always been naturally good at, I don’t know where to say I may have learnt it. Since I was a child I’ve been interested in making beautiful decorative things as a hobby. Things changed when I was in grade 10, I had taken Visual Arts as one of my academic majors and my art teacher at the time was very adamant on art class excursions to artist studios. I vividly remember a trip to bag factory studios and a talk with the late Benon Lutaaya in his studio on one of those small school excursions. That was the first time I understood art as a career. The world and my immediate family had kind of trained me into believing that art is something reserved for the ‘hobby’ category and it’s not something to be taken too seriously. Still, I wasn’t completely convinced, and then I did architecture at Wits for a year and I absolutely hated it, I had friends studying fine art so I would skip my construction lectures and go sit in their classes, and even in architecture school, I was really good at the design and drawing side of things, my lecturer at some point criticised me saying that I design like an artist and not an architect – I took that as a sign and never looked back really.

It just became a ripple effect, I’m still seeing it now. Every time I see South African artists showcasing their work all over the world, doing creative collaborative projects with huge renowned brands like Cristian Dior and Gucci, all of it is affirming that what I’m doing is valuable and that the journey isn’t as simple as selling paintings, there’s a whole world of creativity that I get to unlock, and painting is just the first step of the beautiful journey that is to come.

Now that I’ve completely surrendered to the craft I’m also realising how important art is in anthropological study. It’s a reflection of people and their beliefs and how these beliefs are performed in different times. Art is about politics, it’s about science, it’s about collective memory and psychology, culture conservation – it’s about representation and storytelling. It’s important, and now that I realise its importance I feel a responsibility to share it with the world.

Can you talk about your medium and materials, the stippled way that you create your figures?

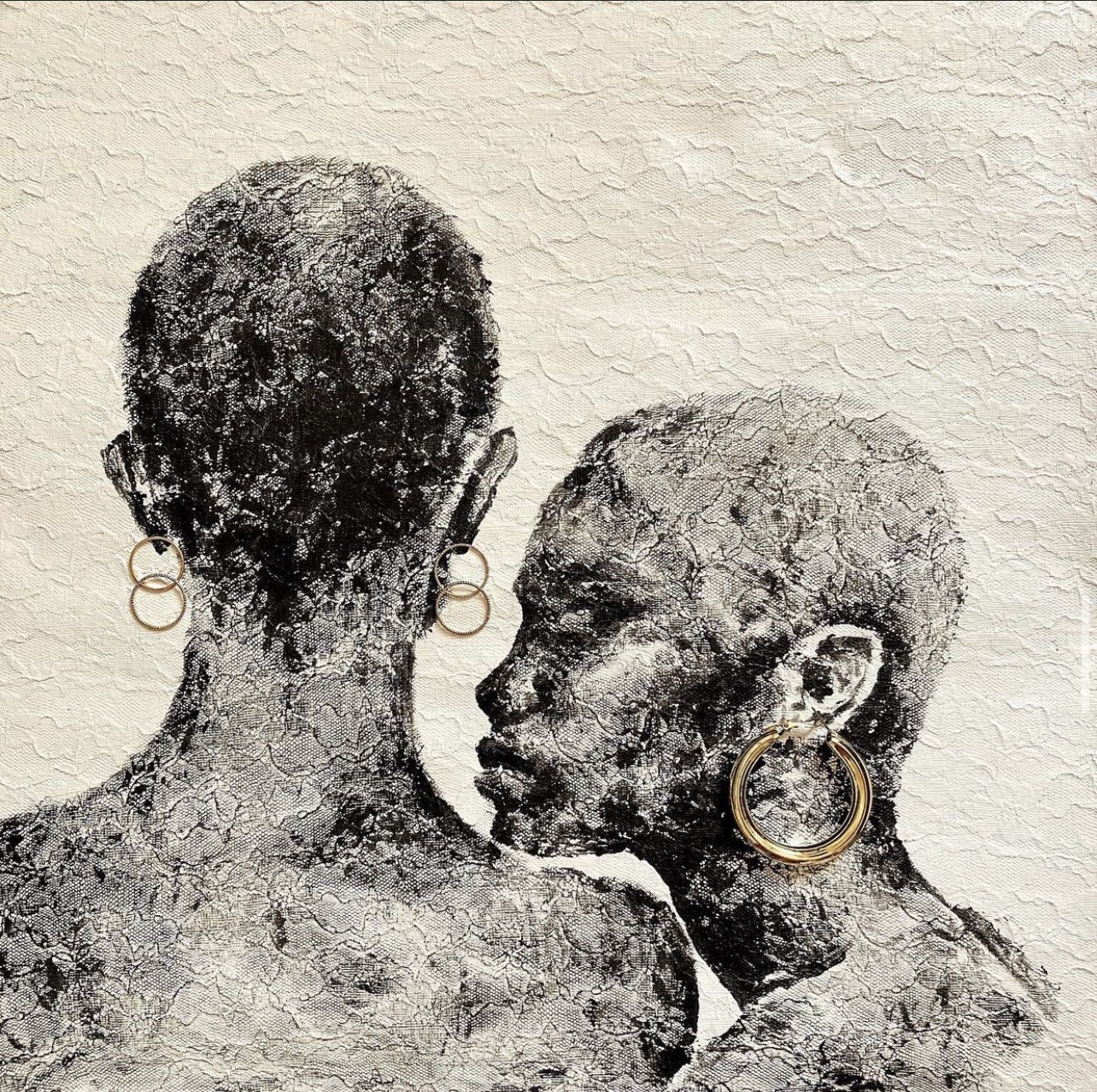

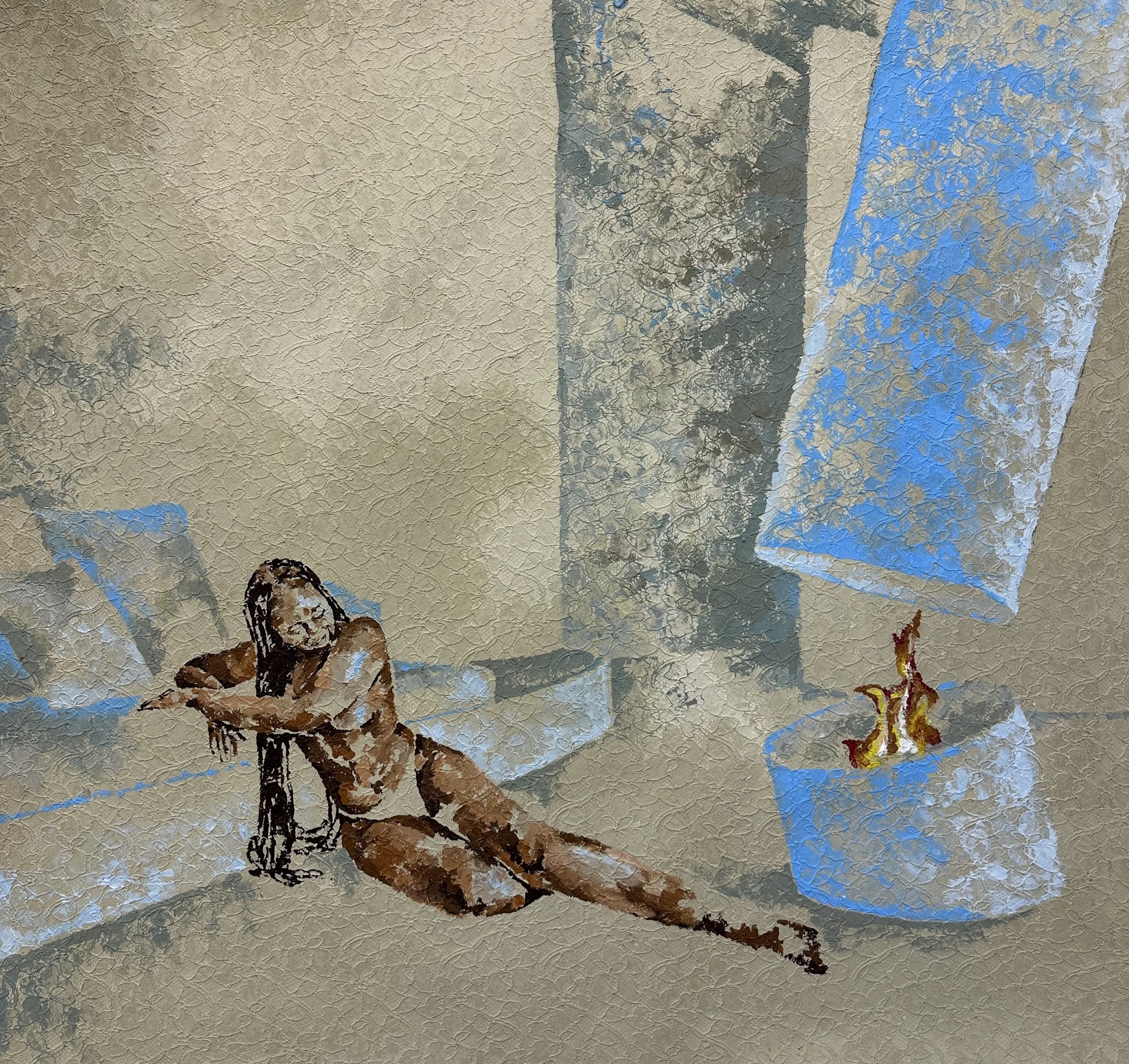

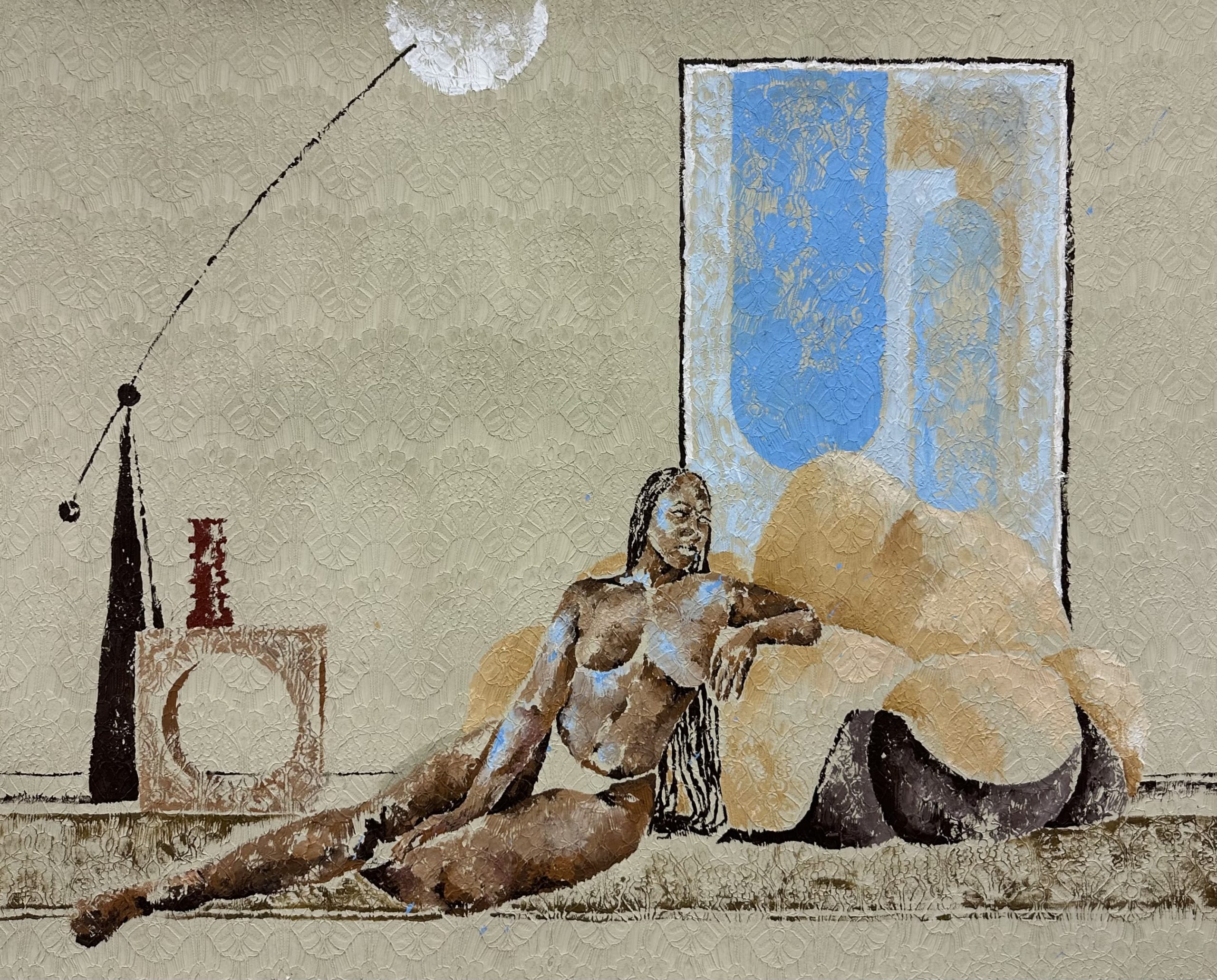

I prepare paper with lace fabric and then paint on that prepared paper. I enjoy this process because it adds a layer of detail to the work that dares you to stare a little longer, and it also has a lot to do with the dimensionality of the subjects I’m presenting. They aren’t simply figures so in my mark making, I try to reflect not just the shape that we see with the eye but to bring forth the complex femininity of my subjects. We’re never just one thing, and telling a layered story with still images is a difficult thing. I use the details on the mark making to present layers of the story to audiences.

Who are the figures and women in your works, and what does it mean to focus on the feminine as your muse?

My work is very autobiographical in its nature, so a lot of the time my work is about my own navigation of my femininity and sensuality in a changing world. So I paint myself and the women in my immediate surroundings because those are the stories I’m reflecting back at the world. It’s also beautiful because my work grows as I grow. I remember switching degrees from architecture to fine art and there was a shift in the kinds of spaces I was in and thus the kind of women I painted changed. In the school of arts I’m coming across bold, more regal women, with brighter hair and larger personalities and now I’ve got a whole series of portraits of women based on the way I see beauty and femininity being performed around me.

I also paint largely for my younger self. In my recent body of work I’m painting women in the nude in imagined luxurious architectural spaces: this is a love letter to young me, telling myself that I, a black girl from the most rural parts of the Eastern Cape, deserve repose, I deserve rest, I deserve to take up beautiful spaces – so that’s what I paint. We need to see ourselves in the ways that we want to exist, it’s a form of manifestation. I had a conversation with a cousin of mine who comes from the context I started in and I remember telling her I wanted a house with an infinity pool and she didn’t understand what that was, and I decided that that’s the kind of thing I want to paint. She’s never seen someone that looks like her in that sort of space, owning or existing around those kind of things so she can’t dream it or work towards it because even if she looks through a magazine with luxury homes, the little white picket fence family in the magazine doesn’t look like her or anyone in her immediate surrounding so she grows up thinking she doesn’t deserve to live like that or she doesn’t belong there: that’s the thing I want to change. That’s why I paint the girls in the fast cars and lace fronts, so my younger self can dream.

What is your vision right now as a young, fine artist in South Africa?

My vision, or curiosity rather, is our collaboration and engagement with other artistic disciplines on a global level. Art isn’t simply about art objects anymore, and I’d like to watch how our potential unfolds. I’m enjoying seeing South African artists doing shows all over the world and collaborating with other large creative enterprises. It’s like we’ve challenged ourselves to take our stories to every corner of this earth and it’s a beautiful thing to be a part of.

Written by: Holly Beaton